Hold On To Yourself

Part I: Finding

Thank you for coming back, or for finding your way here for the first time. However you arrived—I’m so glad you’re here.

My friends over on Medium can read this here.

Hallo Kartoffelkumpel,

Around this time 8 years ago we were dwelling in a sort of antechamber, where fear flickers in silence, denial translates into reassurance, and the body knows what the mind isn’t ready to say. Waiting rooms are built to disguise time. They’re meant to feel temporary, harmless, invisible. But waiting is its own kind of time, one that holds you in fluorescent suspension, never quite before and never quite after.1

Indifferent Clocks

There’s a room with too many chairs, all facing nothing. A television sputtering some live-action remake no one asked for. Somewhere, a child coughs. A printer whirs, stops, starts again. These rooms are made to be visibly invisible. Muted colors, indifferent clocks, a small reception window that reminds you someone is watching even if they aren’t in view and don’t respond to your inquiries. They hand you paperwork that you already filled out online on a clipboard that is too loud and a pen with the last gasp of ink. You’re not meant to be productive.

You’re meant to wait.

And you learn here that waiting is its own kind of time. Not before, not after. Just fluorescent purgatory. No arc, no plot. A clipboard clatters, a name is mispronounced and quietly corrected. Even your breath gets tired of being held. In these rooms, no one says what they’re really thinking. It might scare someone else. It might scare themselves. So we leaf through outdated parenting magazines, nod at strangers, check the stroller straps, check them again.

This place smells like soap and something else…maybe hope? Or maybe fear. No one ever told me how much hope feels like fear. It’s astounding how similar those two things are. Plus it’s hard to tell the difference when you’re mere months into fatherhood and the milestones aren’t tracking the way the book says they should. She sleeps in her carrier and I count her breaths without meaning to. One, two, three—pause. She wasn’t crying. That made me nervous. Why wasn’t she crying? She’d been crying on and off all night, all week. And now she was more peaceful than I’d seen her in a long time. Were we overreacting? She seemed fine now. I think to myself:

If I hold very still, the next thing won’t come.

Across from us, a toddler kicks his light-up sneakers against the metal legs of his mother’s chair. Red. Blue. Red. Blue. The hush of the room holds steady, like too much sound might tilt the balance. A door opens somewhere down the hall. Not for us, but I sit up anyway. Reflex.

The nurse calls a name and the woman with the blinking-shoed child collects her things. The room folds around her absence. Internally I waffle between hoping we’re next and getting all of this over with; and wishing the next name will never be ours, they forget to call us completely, and we go home like nothing happened. Or has been happening. Every night.

I try to read the one of those magazines they put out for—us? What parents are actually reading these? The words blur but I’m pretty sure they’re spelling out a-n-x-i-e-t-y. Tummy time. Milestones. Smiling babies with steady eyes. All the things the Kartoffel isn’t doing.

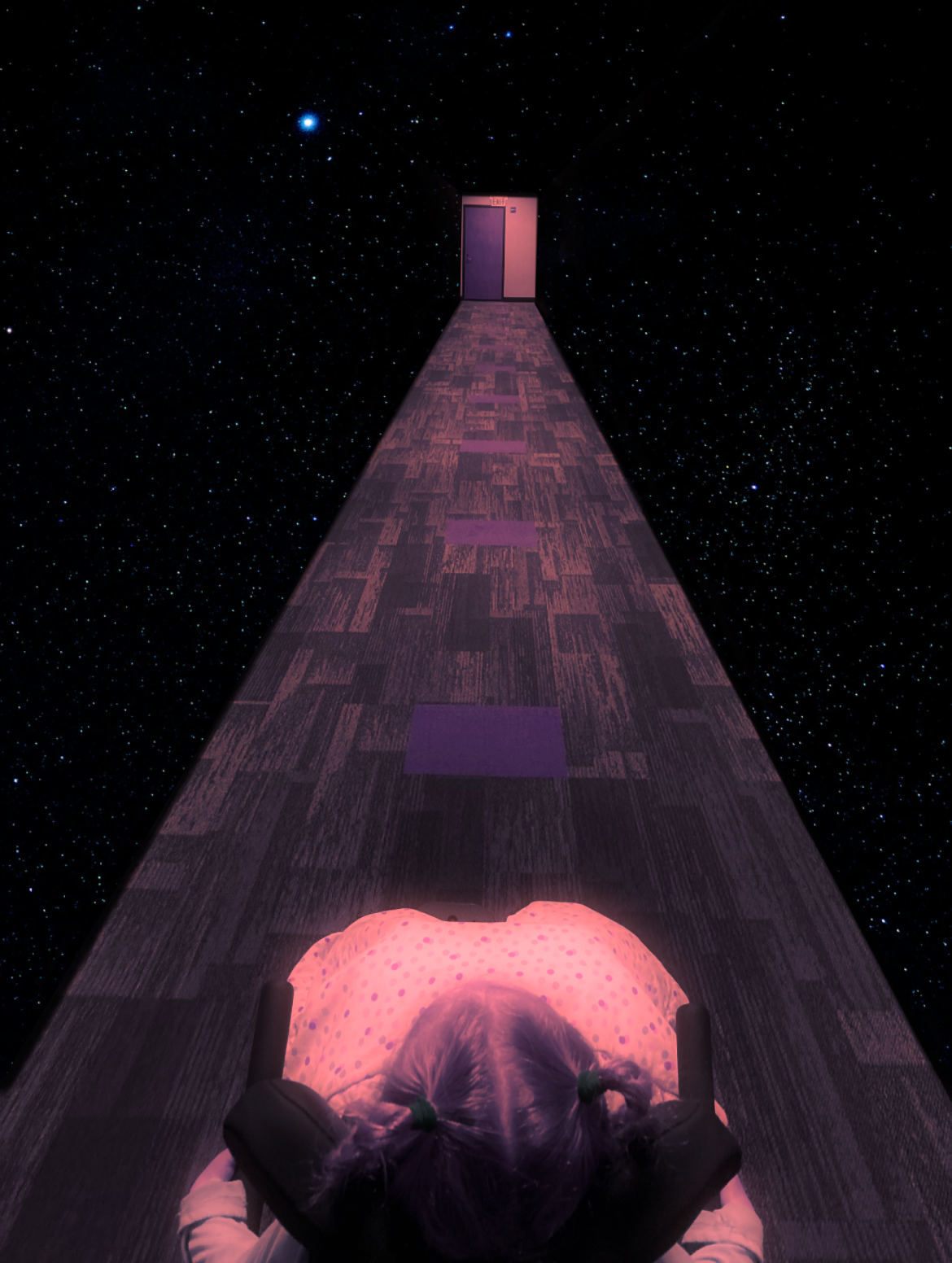

The door opens again, and this time it is our name they call. I lift Emma’s carrier, careful not to wake her, and we follow the nurse down the hall. The lights stretch out ahead of us, a tunnel of dread leading somewhere I’m not sure I want to go. But my feet move forward anyway, because that’s what you do in these places. You wait, and then you follow the voice that calls your name.

Behind us, the blue chairs wait for someone else to count breaths, to flip through magazines without reading them, to listen for the sound of their own door opening. The room holds its breath, suspended in that particular quiet that comes before everything changes. As we sit in our new room I think to myself:

If I hold very still, the next thing won’t come.

Right?

Inside the Thing

The next thing didn’t come then, because it was already there.

That’s what I see now, looking back. Not denial, not ignorance, something less precise. When your body knows first, and your mind spends weeks catching up.

My wife noticed it first. How Emma’s legs were a little too weak. The way her eyes were always a little too glossy. And then, the way her arms would suddenly jerk upward in these brief, blink-and-you’d-miss-it rhythmic clusters, her body folding in on itself like she was trying to protect something small and vital inside her chest.

“This isn’t right,” she’d whisper thinly. I’d watch Emma’s face during these moments, searching for signs of distress, but at this stage she seemed almost peaceful afterward, as if the strange movement had released some kind of pressure.

The pediatrician offered the familiar reassurances: reflexes, gas, nothing unusual, babies are still learning themselves! And maybe that was true or maybe I just wanted it to be. In spite of this I found myself watching her more closely, holding her longer. My arms adjusted to her, unthinkingly. My hands stayed an extra second beneath her head. Her body seemed to ask for more support, as though it were built of different materials.

The episodes became more frequent. More defined. My wife started filming them, collecting digital evidence, trying to name what no one else seemed able to see.

“This keeps happening,” she’d say. “Look at this one, it’s the same exact thing!”

I wanted to believe the pediatrician. I wanted to believe in Emma’s smile, in the innocent individualism of baby development. But watching the footage…

We brought the videos to the next appointment. The pediatrician smiled again. Warm, practiced. “I’m not concerned,” she said, her voice kind but certain. “She’s expressive. First-time parents often worry.”

And yet the worry remained. Not a loud, panicky, sharp worry. Just steady, like a ringing in your ears that you eventually start hearing in your bones.

Other babies were learning to lift their heads, push up on their arms, look around like small explorers. Emma tried, but her efforts carried differently. She’d lift her head for a moment, then let it drop back down, not in frustration but in a kind of resigned exhaustion that made my chest tighten. She seemed to tire faster, fold in deeper. Her body worked differently, even if no one else could see it. I think to myself: If I hold very still…but it wouldn’t matter because we were already inside the thing.

All we needed was the door to start swinging.

Until next time stay safe, stay kind, and know that you are appreciated.

Cheers,

[kartoffelvater]

Did this newsletter resonate with you? Reply with your thoughts or share your own story. And if you know someone who might need these words today, please forward this along.

We wouldn’t be here without you. Every bit of support helps and we appreciate it more than words can say!

I’m trying something a little different. As we make our approach to our Pachyversary the words that are coming to me are more narrative, and so, I thought that this week instead of giving you one big long post to read I’m going to break it up into several parts. I’m not sure how many yet but for now it’ll mean shorter but more frequent posts.

I will probably also have fewer footnotes as many people said they found them distracting. As always, please send me any feedback you have!

Leave a comment