This is Gonna Hurt Like Hell

Part II: Fracture

Thank you for coming back, or for finding your way here for the first time. However you arrived—I’m so glad you’re here.

Hallo Kartoffelkumpel,

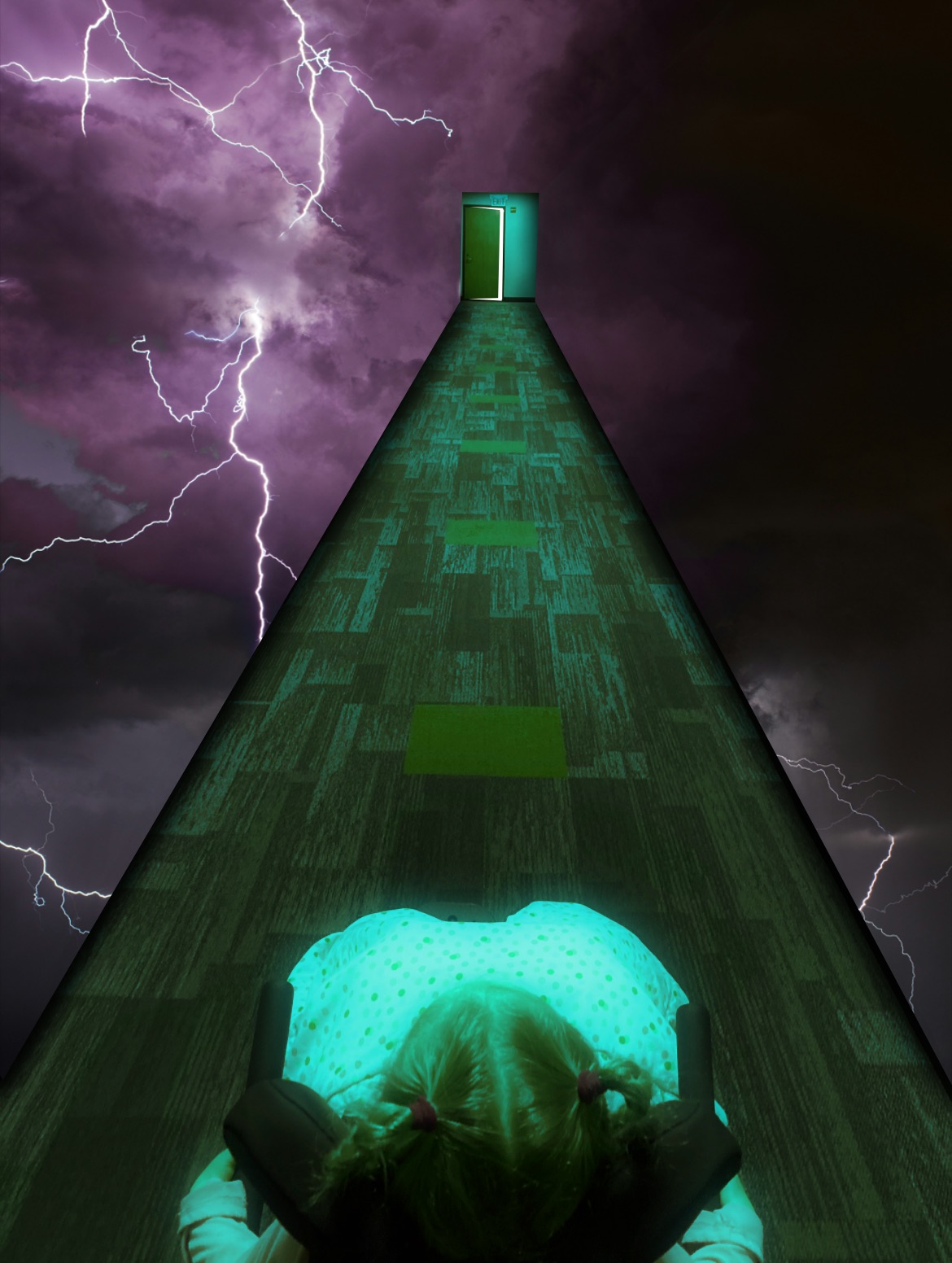

Last time, the waiting room held us in suspension, balanced between silence and fear, denial and recognition. But waiting never lasts forever, because it is not the end. Until you are ready for the end you will be happy to wait, even if you don’t enjoy it. In this second part, the balance shatters. What had been whispered, doubted, and softened by reassurance becomes undeniable. And suddenly we are going through a door we know we’ll never get to walk back out of again.1

You Want My Advice?

The emotional weather of those weeks was thick and heavy, but largely unspoken.2 The kind of atmosphere that makes you speak in half-thoughts and finish each other’s sentences with silences. My wife would start to say something about Emma’s movements, and I’d redirect her gently.

I’ve always been pretty good in a crisis, probably why I got into the line of work I did, and so way back at the beginning, before there was even a diagnosis to worry about, I absorbed the idea that my role was to be calm. To steady. To reassure. I thought I was helping by becoming the ballast, the counterweight. So I practiced the voice of composure, lowered and even, the kind we would so often hear in waiting rooms and doctor’s offices. Bolstered by the advice I was readily given by many I borrowed a certainty I didn’t feel and offered it to my wife as though it could shelter us both.3

It’s fine, it’s nothing, let’s just keep an eye on it.

But the longer I held that pose, the more it pulled me apart. Each episode hollowed me a little more. I knew what I saw, but my words refused to match it. My wife spoke one language—naming what was happening—and I spoke another, one that was built on delay, on soft denial. I told myself I was protecting her from fear, but really I was protecting myself from saying it out loud.

My body told the truth I kept swallowing. The clenched jaw. The breath I didn’t realize I was holding. Knuckles whitening around the stroller handle. Fingers shaking as I clicked the buckle shut. Outwardly I was calm; inwardly I was frayed and flayed every which way. With some distance I can see now how unsteady I was. Split with one voice smoothing over the surface while the rest of me was quickly coming undone.

And all the while the episodes kept coming. As we would soon find out, epilepsy doesn’t wait for you to be ready for it. My wife’s videos multiplied. She’d pause them, show me the moments with the precise flick of her arms, the drained look after. “That’s not normal,” she’d say. And I’d look, and I’d see it. I did. We began to drift. She saw patterns, and I offered platitudes. A new distance grew between us, quiet and sharp. She was learning a new language while I was pretending not to hear it.

We’ll just keep an eye on it.

Because, I promised myself, if you keep very still…

A Language We Had to Learn

Now I don’t know exactly what happened because on this particular visit I wasn’t there but I do know exactly what Emma’s episodes looked like. I know how when it happens your eyes blink without the lids moving. How the air gets sucked out of your lungs and placed on the table before spilling all through the room. How the walls seem to heave and bulge in. How everything pauses. So I know that this time my wife didn’t have to explain or plead or show endless videos.4 This time, the doctor saw it for herself. And I’m sure her professional composure flickered, for just a moment.

Suddenly we had referrals, phone numbers, instructions that felt both impossibly complex and terrifyingly simple.5 We set up the appointment. The door we’d been waiting outside was swinging open.

What happened next exists in my memory like a series of photographs taken from a moving train, in fragments of moments, blurred at the edges, the sequence not always clear.

My wife driving, me watching the GPS wishing it would actually help me navigate my own dread. Emma in the backseat, awake because we’d been told to keep her sleep-deprived. I know I’ve spent quite a bit of your time here convincing you that I had no clue what I was doing as a new parent, but I was pretty sure that keeping your kid from sleeping was the opposite of parenting.

I kept rubbing the sole of Emma’s foot, she hated it but it did the trick and kept her awake each time. She has still never forgiven me for this.

The neurologist had kind eyes. “We’ll need to run a test,” she said. Back down the hallway. Into a small room.

“It’s called an EEG.” Electrodes pressed like flowers into Emma’s scalp. A room lit in sterile blue. Machines humming their quiet intent. It lasted an hour, which I know now is laughably brief for anything definitive.

The EEG finished. The electrodes came off, we went home. A few decade-long days later we got a phone call.

“We want her to be admitted today.”

Today.

The word landed between us like a stone through glass. Not next week, not when we were ready, not after we’d had time to process what we’d just witnessed. Not after I had time to apologize to my wife for not showing that I believed her all those months. Why does ‘I’m sorry’ take so damn long to say? Entire lives have been lived between that ‘I’ and ‘y’.

I and…why?

Today.

My wife was already packing. Diaper bag, bottles, medical cards, socks. Her hands precise, already moving toward the version of herself this new world would require. More images flash in my mind of Emma in a hospital gown too large for her, the air thick with that damn antiseptic uncertainty. The shape of my wife’s hand holding mine as we drove back to what would become our new home away from home.6

The Other Side

Later, much later, we would learn that our pediatrician had never encountered Emma’s condition in her decades of practice. She had done exactly what she’d been trained to do, followed the protocols that work for most children, most of the time. It wasn’t her failing—it was the system’s, the way certainty is supposed to work in medicine, the way we’re taught to trust in the familiar patterns until something unfamiliar breaks them open.7

I sat in that hospital room and watched Emma sleep. She was still Emma, still the baby who melted into my chest when I held her, still the one who could calm me with her chattering and the way she’d turn toward my voice with a look at me with a face somewhere between disappointment and disgust. But there was also a way about her that was becoming something else, something that required machines and specialists and words and procedures I was going to have to learn.

There are lots of cliches about opportunity, and knocking, and doors. The door that opened for us still has lots of opportunities but they aren’t the ones we wanted, even if they are the ones we need. And now we are on the other side. We didn’t even have to knock.

I know we’ll never get to leave the way we came in.

Those too many chairs and indifferent clocks are already waiting for the next name to be called. And maybe, if the people sitting in them hold very still…

Until next time stay safe, stay kind, and know that you are appreciated.8

Cheers,

[kartoffelvater]

Did this newsletter resonate with you? Reply with your thoughts or share your own story. And if you know someone who might need these words today, please forward this along.

We wouldn’t be here without you. Every bit of support helps and we appreciate it more than words can say!

Footnotes are back because pro-footnote comments were more voluminous than anti-footnote comments and this is a shabby utilitarianism production here. You want them gone again? Let me know.

There is a nothingness to the words we would use when we are living their concept, it is not until after we have moved through the fire, scathed, that we are free to use what words we will. So much of what we go through feels like little more than something to go through until we have gone through it, then the words come.

There is a much broader and deeper conversation here about inter-generational transmission of acceptable behaviors compounded by cultural norms surrounding how men and women are ‘supposed’ to respond to things. It is an important conversation that deserves much more nuance than can be afforded to it here, but if you have thoughts about it now please let me know.

She did shout, though. My wife is a total badass.

I understand that the narrative as I have laid it out here has my wife taking on a more instrumental rather than embodied role. That’s because this is my memory, not hers, and I wouldn’t presume to know what was going on inside her head at the time (though we have talked a great deal about it). I am respecting her story by not assuming it is also mine, y’all should encourage her to start her own blog (I’m looking forward to hearing how much she loves me telling you all to do that).

There is a hefty dose of ‘parents vs doctors!’ rhetoric already streaked across this community but I want to be clear that I am not blaming the doctor. I did then, but I am not now. To start, blame requires the absolute minimum amount of effort and once I sat and reflected for any amount of time it was no longer an answer. Secondly it completely externalizes the locus of control in often the least productive way and so functionally achieves nothing. Third, it is far more complicated than just ‘It was the doctor’s fault’ in most circumstances (straight medical malpractice notwithstanding). It’s more complicated than even just putting it on ‘the system’ because what the heck does that even mean? Most of this comes down to fundamental understandings of what is real, how or if we can even know what is real, what it means to be human, and how we are supposed to live. And if you have clear, concise answers to those questions that can be applied universally without any danger of marginalization or misinterpretation there will be several religions and philosophical schools of thought (literally all of them) who would be very interested. I don’t. So I am doing my best to live with and understand people instead of blaming and cutting them off. Yeesh this probably needs a whole blog post on its own, maybe a whole podcast series…

Leave a comment