Feeling the cost of survival in the quiet of home.

Thank you for coming back, or for finding your way here for the first time. However you arrived—I’m so glad you’re here.

Hallo Kartoffelkumpel,

There is a specific kind of exhaustion that only shows up once you’ve finally sat down. It’s a tired that waits until the room is quiet to remind you how heavy your own limbs have become. Lately, I’ve been thinking about how we carry ourselves through the days we never thought we’d have to survive, and what happens to that momentum when the immediate need for it vanishes. It’s a strange thing to realize that sometimes the hardest part isn’t the climb itself, but the way your body shakes once you’ve reached the plateau. I’m checking in on all of you navigating these heavy after-moments (and if I haven’t checked in on you and you would like me to, let me know).

It took a few days.

We came in from the cold, yes. We slept in our own house. We made coffee in our own kitchen. But those first days after discharge from the PICU felt more like a relocation than a return. I didn’t really feel I could say we were home yet. For days our bodies still pitched forward, waiting for the next interruption. Adrenaline doesn’t care about addresses. It lingers. It keeps its own calendar. Makes your fingers restless.1

It was later, a handful of nights in, when stillness finally found me.

The living room was dark except for the Christmas lights we had draped along the footboard of her new hospital bed. We’d just had it delivered. It was an abrupt, practical upgrade that arrived with the authority of necessity. It made caring for her easier. It also rearranged the room around a truth we could no longer pretend was temporary.

We slept there together for a while. My daughter in the bed. My wife and I trading the couch and the recliner. The house held us, but tentatively, like it wasn’t sure yet what version of us had returned.

My daughter slept (or really more rested, or maybe hovered?) in that ambiguous space we now call stable, though I’m no longer certain what that word means outside the hospital. Exhausted, but holding. Alive in a way that feels provisional only because everything does now.

The absence was loud.

We still had the machines that breathe with her, the monitors that translate her body into numbers. But now there were no nurses passing by with practiced glances, no quiet reassurances spoken fluently in acronyms. Just us. Just the dark. Just the soft, uneven sounds of a house settling around a child who has never really fit inside ordinary definitions of safety.

I realized then that what I missed was not the crisis, but the company.

In the PICU, vigilance was shared. At home, it became solitary again. Just us. There was no one to hand the watch to. No one to confirm that what I was hearing—or not hearing—was acceptable. Every sound felt suspicious. Every silence required interpretation.

I watched her chest rise and fall in rhythm with the vent, the Christmas lights reflecting faintly off the metal rails of the bed. The cup of water on the coffee table caught my eye. The glass looked too thin. Too breakable. The same feeling I’d had in the hospital, now relocated, domesticated.

My hands were still shaking.

There was nothing left to hold.

During the crisis, everything had been sharp. Time narrowed. Attention hardened. My body knew exactly what to do because it had no other choice. Stand here. Listen harder. Stay ready. Urgency edited the world down to its essentials.

Home removed the editor.

Stillness arrived without instructions. The danger had receded, but it hadn’t left. In the PICU she is under a microscope, but here it felt more like I was looking at her through the wrong end of a telescope. The house was quiet in a way the hospital never was. Not a negotiated hush, but an ordinary one, the kind of quiet you might imagine as you hum along to O, Holy Night. The hush people usually associate with peace and poems.

It didn’t feel like peace.

High alert had ended, vigilance hadn’t. My body didn’t know how to downshift. It kept scanning, listening for alarms that didn’t exist, replaying moments that hadn’t gone wrong just to be sure. And then there is that awful aching.

It didn’t begin all at once or dramatically. It settled in like dampness. My jaw hurt from days of clenching. My shoulders sagged as if something heavy had been removed without warning. Even standing at the sink felt like effort. Ugh, the damn sink.

The sink was full of mugs. Laundry sat unfolded on the couch. In the hospital, coffee comes in paper cups you throw away. You wear the same clothes for days. The world is pared down to what matters most, and everything else politely disappears. At home, it all returns at once. Dishes. Clothing. Trash needing to be taken out. Dust needing to be swept. The small maintenance rituals of a life that assumes continuity.

I stood there longer than necessary, staring at the mugs, unsettled by how uncannily fragile this version of normal felt. As if I was washing with someone else’s hands and the act itself might ask more of me than I had left to give.

We talk a lot about resilience as endurance. About holding fast, pushing through, staying upright no matter the cost because we don’t have any other choice, because you would do it too if you were in my shoes. That story makes sense when everything is actively falling apart. Endurance explains how you survive the moment when the stakes are unmistakable.

It explains far less about what comes after.

Stillness exposes a different kind of fragility. Without urgency to organize you, the cost becomes visible. You are left alone with the residue of attention. With the knowledge of how narrowly things held. With the unsettling realization that the part of you trained for crisis does not automatically know how to live without it.

My daughter has always survived through yielding, through reliance, through systems and people and hands that hold her precisely because she cannot hold herself. That web carried her through the worst of it.

Now, at home, that same web felt thinner. Still present, but more willowy. Less obvious. The knot still tied. The net still holding. Just no longer announced by alarms or shifts or rounds or visitors. And for the first time in days, I wasn’t pulling against it.

There was grace in that, but it wasn’t comforting.

The bracing didn’t end so much as give out. I had been standing longer than I knew, and when the weight finally settled, the cost arrived without explanation. What had been spent could no longer hide behind function or necessity. There wasn’t a need to tread water and so the water calmed. But still water does not mean shallow water. Sometimes it means depth without markers.

I wondered, not for the first time, whether this ache was something to be fixed or something to be honored. Whether soreness was a sign of weakness or evidence that my body finally believed it was allowed to feel again.

The lights on her bed glowed softly. The house breathed around us. Outside, the holiday season was winding down, but here the decorations lingered, cradling a joy that felt tentative, careful, real in a way that refused performance.

Tomorrow would ask again. I knew that. Care that heads in the opposite direction of recovery never ends. Crisis is never far. Stability—whatever that word means now—is always provisional. But for this moment, there was this narrow, shattered stillness that could bear weight.

I sank into the couch between piles of clean-but-heaped clothes for an uneasy rest.

Until next time, stay safe, stay kind, and know that you are appreciated.

Cheers,

[kartoffelvater]

Did this newsletter resonate with you? Let me your thoughts or share your own story. And if you know someone who might need these words today, please forward this along.

We wouldn’t be here without you. Every bit of support helps and we appreciate it more than words can say!

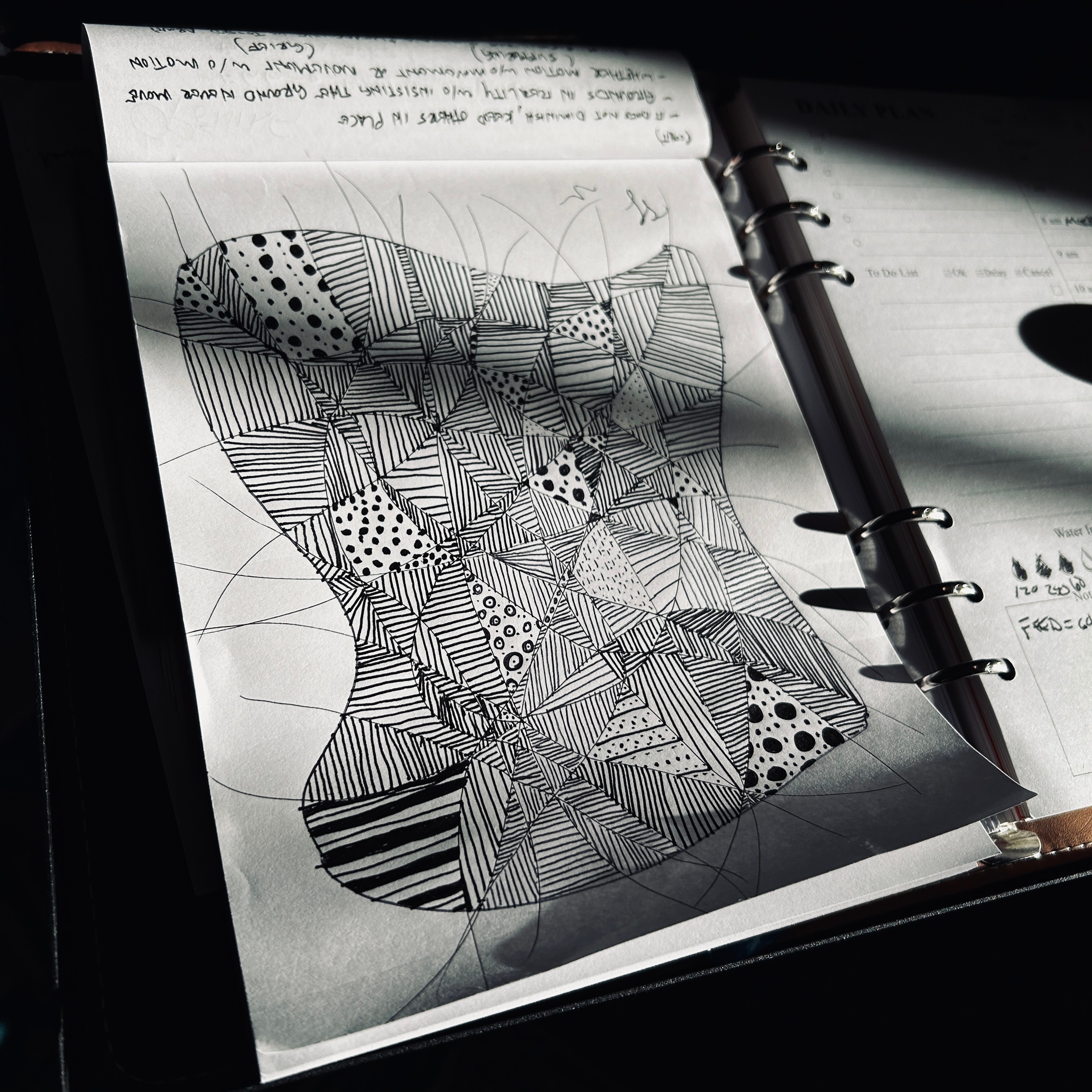

- The doodle in the picture is one of many that come from restlessness. And if you look closely, you can see the first draft for another essay scribbled at the top, first drafts are always written out by hand. There’s something about pen on paper that brings words out. ↩︎

Leave a comment